Are you tired of winning yet?

The arts made me a loser

I didn’t grow up on art or music. That came later. My dad was a pastor. My mom ran the school we attended on the church campus. We were a megachurch household in a rust belt city. On Halloween we would hide away with the lights off and curtains drawn. That was the Devil’s holiday. The only culture we consumed had the Focus On The Family seal of approval. They flagged any media that contained violence, sexual content, or just ungodly undertones. SpongeBob didn’t make the cut. My brother and I were limited to Christian rap, Veggie Tales, and the Left Behind series until we were 13.

I did spend a lot of time playing sports. And one of the things I loved about playing sports was how tight the feedback loops were.

Miss that fadeaway jumper? Unforced error straight into the net? Drop a 10-yard pass that should've been a gimme running that wheel route? Adjust your form. Try again. And again. And again. Until you get it right. Until it's second nature.

I learned a lot about winning and losing playing sports. The real winners know that losing is temporary. Just sink the next shot. Win the next game. There's always next season. You’ve got your team to support you, your coaches to critique you, and your trainers to guide you through your reps.

Losing sucks, but at least it’s clear.

I can succeed. I will succeed. I must succeed. But so must the other guy.

The Yankees pray to God:

“Lord, please grant us the strength and resolve to do our best…”

But so do the Braves.

- From Stuck In The Middle With Bruce by John F. Rizzo. Start here for context.

The arts made me a loser

As I grew older I lost interest in sports and started making music. I opened a music venue and gallery with some close friends. I moved to New York City and started a job in the arts.

As I flung myself into the arts, the word losing slowly vanished from my vocabulary. It wasn’t about winning or losing. I was interested in exploring and experimenting. The finer things in life.

I didn’t recognize it at the time, but I was still playing a game. Compared to my time playing sports, the feedback loops in the arts were practically nonexistent. My work involved a lot of grant writing and ongoing conversations with decision makers at cultural institutions. Lots of waiting.

Imagine shooting a three-pointer in zero gravity and having to wait months to see if you sank the basket. Now imagine playing a full four quarters at that pace. I’d rather be in Hell.

It was never clear to me if I was winning or losing, but I now know that there are in fact winners and losers in the arts. The industry likes to obscure the rules of engagement. It’s cooler that way, more mysterious. A select few make careers out of it. There are pop stars, indie darlings, and outsider artists. You just have to choose your character.

This obfuscation is connected to a larger cultural trend. Large swaths of arts industries are built around the assumption that the market isn’t a sufficient tool to determine the value of a work. Artists classically hate money and, in turn, hate anything to do with the market. So that valuation lies elsewhere.

Writers at newspapers, magazines, and blogs once helped to determine value. But that has slowly shifted. There was a move a few years back to eliminate scoring on the major review sites. They removed user comments too. They got rid of the scoreboard. They got rid of the competition. Eventually they just cleaned house and got rid of the writers too.

The valuation of art now leans on engagement metrics. I don’t think this is inherently a bad thing. But the incentive structures and feedback loops haven’t been properly optimized across the various arts industries yet. And both these industries and the artists themselves are often incredibly resistant to any attempts at creating new incentive structures. This peaked most recently with the fiercely anti-NFT sentiment among many artists.

What’s worse than losing? Losing and not knowing it. Even worse, losing but thinking that you’re winning.

Playing winning games

In more recent years, I’ve made less music. Sports have me hooked again. And even my work has shifted too. In 2020, FuturePerfect, the studio where I worked for 10 years, pivoted away from producing projects in the art world. We founded a startup. A year later we set our sights on VR. And then, a year after that, we made a video game. Now I’ve started a company with my brother to make our own games. More on that in a later post.

For me, making a video game is closer to playing sports than it is to making art or music. Especially making a game for Steam. Steam is a rare breed in terms of platforms. In contrast to other platforms like TikTok and YouTube, Steam is anti-slop. The algorithms are incredibly well-tuned. The incentives of the company, game creators, and consumers are very well aligned. The market on Steam has clarity. Sell and you’ve won. Flop, and you’ve lost.

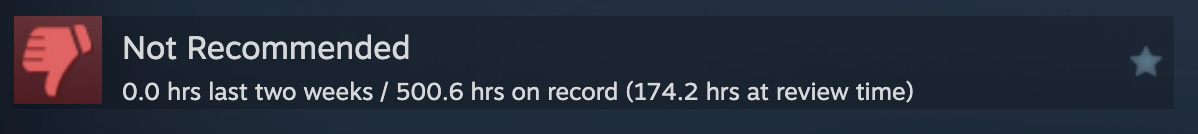

One of the best things about Steam’s review system in particular is the proof of engagement. Every review includes a playtime counter, showing exactly how many hours the reviewer has put into the game. This is what good incentive design looks like.

More importantly, Steam’s algorithm doesn’t just amplify popular games indiscriminately. It fine-tunes recommendations for superfans of specific genres. The right audience is almost guaranteed to come across your game.

Steam has 132 million monthly active players. Most of them are eager to try something new. Some will sink 500 hours into a game only to give the most detailed negative review you’ve ever seen. And these reviews matter. They feed into the Steam algorithm, shaping a game’s visibility. The better the reviews and the higher the playtime, the more Steam pushes the game to new players.

Part of the reason I like making games is because each game serves as a problem-creating machine. Making games is hard. It’s hard because you made it hard as the developer. You spawned these problems from the blank canvas. And now you must come up with the tools to solve them. And the solutions. You control the feedback loop. It’s as tight as you want it to be.

In work, I am now solely focused on tight feedback loops and clear win-loss outcomes.

I’m currently reading James Dyson’s first autobiography, Against The Odds. He had a lot to say about this. Talking about Jeremy Fry, his mentor, Dyson said:

He did not, when an idea came to him, sit down and process it through pages of calculations; he didn't argue it through with anyone; he just went out and built it.

So it was that when I came to him, to say, 'I've had an idea,' he would offer no more advice than to say, 'You know where the workshop is, go and do it.'

But we'll need to weld this thing,' I would protest. 'Well then, get a welder and weld it.' When I asked if we shouldn't talk to someone about, say, hydrodynamics, he would say, 'The lake is down there, the Land Rover is over there, take a plank of wood down to the lake, tow it behind a boat and look at what happens.’

College had taught me to revere experts and expertise. Fry ridiculed all that; as far as he was concerned, with enthusiasm and intelligence anything was possible. It was mind-blowing. No research, no 'workings', no preliminary sketches. If it didn't work one way he would just try it another way, until it did. And as we proceeded I could see that we were getting on extremely quickly. The more I observed his method, the more it fascinated me.

Losing is inevitable, but it’s not always clear. My goal is to make it clear. I will find the L and take it. I’ll play again. And I’ll win next time.

Go Bills