Six months or bust

Making games faster

In a brief article on PC Gamer, Aggro Crab studio head Nick Kaman describes how their recent hit, Peak, was born from a feeling of jealousy.

“[It] turned everything we know about game development upside-down,” Kaman says of making Peak. He continues:

At the time we were on the precipice of launching our biggest game ever, Another Crab’s Treasure—an intense 3+ year-long project that burnt a lot of us out. While it was a success, Content Warning [the co-op survival horror game that inspired Peak] was a much bigger one made in MUCH less time.

Another Crab’s Treasure sold an estimated 500K copies while Content Warning sold over 2 million copies. According to Landfall’s press release, Content Warning was developed in just three months, between February and April 2024.

Three months is absurd… I’m jealous too.

Aggro Crab went on to develop the bulk of Peak in one month during a game jam in Korea earlier this year. It sold 5 million copies in its first month.

Now I’m really jealous. But lucky for you, dear reader, I’m just curious enough to put that aside and dig in.

Let’s look at some numbers…

One useful way to compare these games is by calculating how much value each project created relative to the development time and team size it required. I’ll call this metric Monthly Revenue Efficiency (MRE): estimated revenue generated per month per team member. We can do some rough back-of-the-napkin math using sales data from GameDiscoverCo to calculate the MRE for each game. It’s important to note that these are very rough estimates:

Another Crab’s Treasure

Development length: Over 36 months

Core team: ~12 people

MRE: $25K

Content Warning

Development length: 3 months

Core team: ~5 people

MRE: $2M

Peak

Development length: ~4 months

Core team: ~7 people

MRE: $1.7M

From the outside looking in, these three games are all massive successes. It’s every indie developers dream to sell hundreds of thousands let alone millions of copies, so it might seem strange to hear Kaman talk about burnout with 500K copies sold. But I appreciate the honesty. Once you factor in salaries, overhead, and development costs, it’s possible that Aggro Crab made much less profit from Another Crab’s Treasure than they would’ve hoped after three years in development.

Let’s apply the same back-of-the-napkin math with my climbing game released earlier this year (which I’ve written about in detail here and here).

Void Climber

Development time: 12 months

Core team: 3 - 4 depending on the phase

MRE: $7

That “$7” isn’t missing an M at the end. Or even a 0 followed by a K. That’s seven dollars MRE… all in.

Not only that, 12 months is a bit of an understatement. If you include our two cancelled prototypes, the total development time was more like 36 months. For an indie team aiming to make a commercially viable game, this is a complete disaster. So what can we learn from this?

Steam is filled with all sorts of these games, but you wouldn’t know it just casually browsing the store. There are thousands of them buried in the depths of the platform that failed to make even $1,000 in lifetime gross revenue. There’s a quiet, poisonous risk that grows with every month added to your development timeline: scope begins to creep in, returns start to shrink, and you often won’t notice until it’s too late.

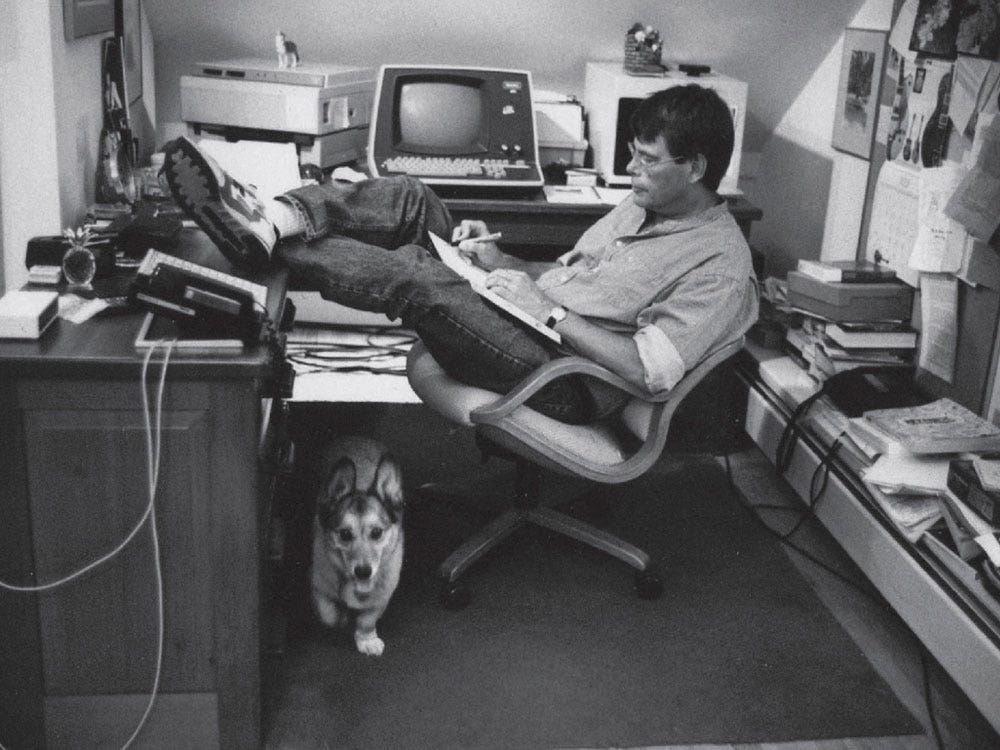

Peak and Content Warning bless us with a perfect antidote to this poison: extremely short development timelines. In On Writing, Stephen King describes a similar rigor when writing his first drafts. He says:

I believe the first draft of a book—even a long one—should take no more than 3 months, the length of a season. Any longer and—for me, at least—the story begins to take on an odd foreign feel, like a dispatch from the Romanian Department of Public Affairs, or something broadcast on high-band shortwave during a period of severe sunspot activity.

Describing his regimen in more detail, he says:

I like to get ten pages a day, which amounts to 2,000 words. That’s 180,000 words over a three-month span, a goodish length for a book—something in which the reader can get happily lost, if the tale is done well and stays fresh. On some days those ten pages come easily; I’m up and out and doing errands by eleven-thirty in the morning, perky as a rat in liverwurst. More frequently, as I grow older, I find myself eating lunch at my desk and finishing the day’s work around one-thirty in the afternoon. Sometimes, when the words come hard, I’m still fiddling around at teatime. Either way is fine with me, but only under dire circumstances do I allow myself to shut down before I get my 2,000 words.

Strange Scaffold studio head Xalavier Nelson Jr. also understands the importance of a tight development timeline. In an interview with Thomas Brush, he describes how he and his team made their incremental horror game CLICKOLDING with a budget of just $25K. The game took a month and a half to build, a schedule they were determined to keep from the start. Nelson Jr. says:

If at every step you're like “well [we] have 3 weeks left to make this game [so] we [won’t] choose a solution to any problem that makes it more than 3 weeks”, then it turns out you can ship that game in 3 weeks

He continues:

You can make a game in three days if you build the type of game you can make in three days

So besides making a great game (easy enough), your other herculean task is to make your development process as constrained and efficient as possible. How do you do this?

One way is to identify what Richard Rumelt, in Good Strategy Bad Strategy, calls leverage: your ability to concentrate limited resources at a critical point to create outsized impact.

A good strategy draws power from focusing minds, energy, and action. That focus, channeled at the right moment onto a pivotal objective, can produce a cascade of favorable outcomes. I call this source of power leverage.

Archimedes, one of the smartest people who ever lived, said, “Give me a lever long enough, a fulcrum strong enough, and I’ll move the world.” What he no doubt knew, but did not say, was that to move the earth, his lever would have to be billions of miles long.1 With this enormous lever, a swing of Archimedes’ arm might move the earth by the diameter of one atom. Given the amount of trouble involved, he would be wise to apply his lever to a spot where this tiny movement would make a large difference. Finding such crucial pivot points and concentrating force on them is the secret of strategic leverage.

Knock loose a keystone, and a giant arch will fall. Seize the moment, as James Madison did in 1787, turning colleague Edmund Randolph’s ideas about three branches of government with a bicameral legislature into the first draft of the Constitution, and you just might found a great nation. When the largest computer company in the world comes knocking at your door in 1980, asking if you can provide an operating system for a new personal computer, say, “Yes, we can!” And be sure to insist, as Bill Gates did in 1980, that, after they pay you for the software, the contract still permits you to sell it to third parties. You just might become the richest person in the world.

In general, strategic leverage arises from a mixture of anticipation, insight into what is most pivotal or critical in a situation, and making a concentrated application of effort.

We’re just trying to make a good game, not “found a great nation”. But I promise, Rumelt’s description of leverage is just as applicable to you as it is to Bill Gates. I’ll quote Rumelt again: “Given the amount of trouble involved, [you] would be wise to apply [your] lever to a spot where this tiny movement would make a large difference.”

You must know your team’s skillset intimately, pick a genre you know well, come up with an idea that sticks, define an appealing art style, and then execute excellently. Skillfully applied leverage is how a game built in three months can earn four times more than one that took three years.

On a recent episode of his podcast Dithering, Ben Thompson relates NBA playoff coaching strategies to Apple’s need for a restart after their failed Apple Intelligence launch earlier this year:

When a 7-game series kicks off, game one happens and sometimes the team that was expected to win loses game one. And the big question is: should the coach make an adjustment or do the players just need to play better?

The equivalent in game development is: is your idea bad, or do you just need to execute better?

Recently announced co-op job simulator Roadside Research is a perfect example of how rapid execution on a good idea can, as Rumelt says, “produce a cascade of favorable outcomes.” Hans (I couldn’t find his last name anywhere), the Lead Publishing Producer at Orbo Interactive, details in a thread on X how Roadside Research reached 60K wishlists in one week.

Hans describes their rigorous timeline saying: “Cybernetic Walrus have been developing the game for 2 months now, and limiting scope on what the trailer would show was vital to making it on time.”

I’ll leave you with the team’s one-page proposal for the Roadside Research trailer (then called “Alien Game”), which has surpassed 10 million views across social media platforms.

romania mentioned 🦅🦅🦅🦅🦅