The anti-sellout psyop

Are successful people psyoping you into thinking selling out is bad?

Spend a bit of time on the indie games side of X or Reddit and you’ll inevitably encounter a vocal majority of developers who are furiously opposed to following trends in games. These developers see indie games as a medium for authentic self-expression free of commercial interests, and are quick to stamp out any talk of the latest hot microgenre hitting the new and trending chart on Steam.

The most recent example of this can be seen in the countless replies to a relatively innocuous post on X by indie developer and aspiring influencer Gorka Games. In this post, the OP argued that solo developers shouldn’t make big open world games and instead should make games in trending genres like friendslop. The post went viral, with developers eagerly filing in to give their take on why Gorka’s advice was bad and offensive. Their takes ranged from thoughtful to somewhat incensed. Well… mostly incensed. Here’s a few:

Developer of the upcoming extraction shooter Beautiful Light (760K wishlists) responded decrying that you shouldn’t chase success, but you should follow your passion:

Developer of the casual digging game Cozy Holes (est. $3K gross) argued that you should buck trends and “make something you love, make something authentic to you.”

Developer of the upcoming post apocalyptic exploration game Garbage Country (72K wishlists) kept it concise:

I could rattle off a few more, but you get the point. To summarize the nearly 200 replies and quotes:

Chasing success is morally bankrupt

Following trends is morally bankrupt

Caring about what players like is morally bankrupt

Crazy stuff if you ask me. Why do so many indie developers think this way? It’s not like players are dying to bear witness to [insert random developer]’s authentic self. Trends are trends because people like them. Players are pleased, even thrilled, to get more games in genres they love. Sales figures and reviews for recent hit games in trendy genres like RV There Yet (est. $20.6M gross) and CloverPit (est. $10M gross) prove this. While the thread from Gorka Games is a little clunky, it echoes perspectives shared by prominent games market analysts Chris Zukowski and Simon Carless. Simply put: make a great game in a proven genre that players love and you’re more likely to find commercial success. Seems pretty uncontroversial.

Yet, the anti-trend trend marches on. But don’t get it twisted… this sort of sentiment isn’t unique to games. It’s a tale as old as time.

In the early 2010s, I ran a DIY music venue and gallery with some close friends and became intimately familiar with the concerns of independent artists. They were the same then as they’ve always been: strongly held beliefs in the value of individualism, authenticity, and self-expression and a repulsion to selling out. Making something for yourself, your friends, or for the scene? That’s good. But chasing success among the masses? That’s bad.

In August earlier this year, the popular fashion and culture newsletter Blackbird Skyplane offered their own version of this all-too-familiar argument against selling out (excuse their idiosyncratic and slightly hard to parse writing style):

So we reject the widespread attitude that Success = Major Bag Getting and “Big Things Coming.”

And what’s heartening to us is that we’re not alone. It can be easy to forget, because as a society it feels like we’re drowning in counter-evidence, but lots of people wish that small, special things could just stay that way, instead of their creators saying yes to every check, expanding senselessly while “chasing 10x,” and putting a bunch of dumb s--t into the world that no one asked for and no one wants.

Please be clear: We are rightly regarded as the Most Unsanctimonious sletter out. But we think the anti-sellout ethos is tight, and worth talking about, especially here in 2025, long past the concept’s supposed expiration date — not least because it can help make all of us feel less cynical, defeated, lonely and insane.

Blackbird Skyplane is #2 on the bestselling fashion charts on Substack. They’ve had profiles in the New Yorker, The New York Times, and Vanity Fair. It’s hard to know exactly, but they probably make high five figures to low six figures per month on Substack. Not bad for a team of two.

Why is it that the loudest sellout haters are often those who have already found great commercial success? Don’t fall for their anti-sellout psyop.

In their post, Blackbird Skyplane continue by offering up Billboard-charting musician Mac DeMarco as the ultimate anti-sellout icon. They highlight his recent rejection of big arena shows, in favor of DIY venues and share a recent New Yorker profile that frames DeMarco’s anti-sellout moves as refreshing and radical:

It’s easy now, possibly advantageous, not to think too critically about the machinery that motivates culture, especially when nobody has to worry about getting called a poser or a sellout. Anything goes. In that context, DeMarco’s gestures at sovereignty feel less cranky and more radical. He is simply trying to reclaim some ground.

In the same New Yorker profile, DeMarco goes on to explain that “Purity and cohesiveness are more important to me at this point than if people like the songs.” To DeMarco, songs aren’t for listeners. Sounds familiar. For the take-givers in Gorka’s viral post, games don’t seem to be for players either.

Thankfully, I have some thoughtful counter examples to tear us away from all this madness. Contrary to what Blackbird Skyplane or Mac DeMarco might have you believe, making music for listeners and games for players is just fine. And making money and reaching the masses while doing so should be celebrated. Economist and author Tyler Cowen explains in his book In Praise of Commercial Culture published in 2000:

Bach, Mozart, Haydn, and Beethoven were all obsessed with earning money through their art, as a reading of their letters reveals. Mozart even wrote: “Believe me, my sole purpose is to make as much money as possible; for after good health it is the best thing to have.” When accepting an Academy Award in 1972, Charlie Chaplin remarked: “I went into the business for money and the art grew out of it. If people are disillusioned by that remark, I can’t help it. It’s the truth.”

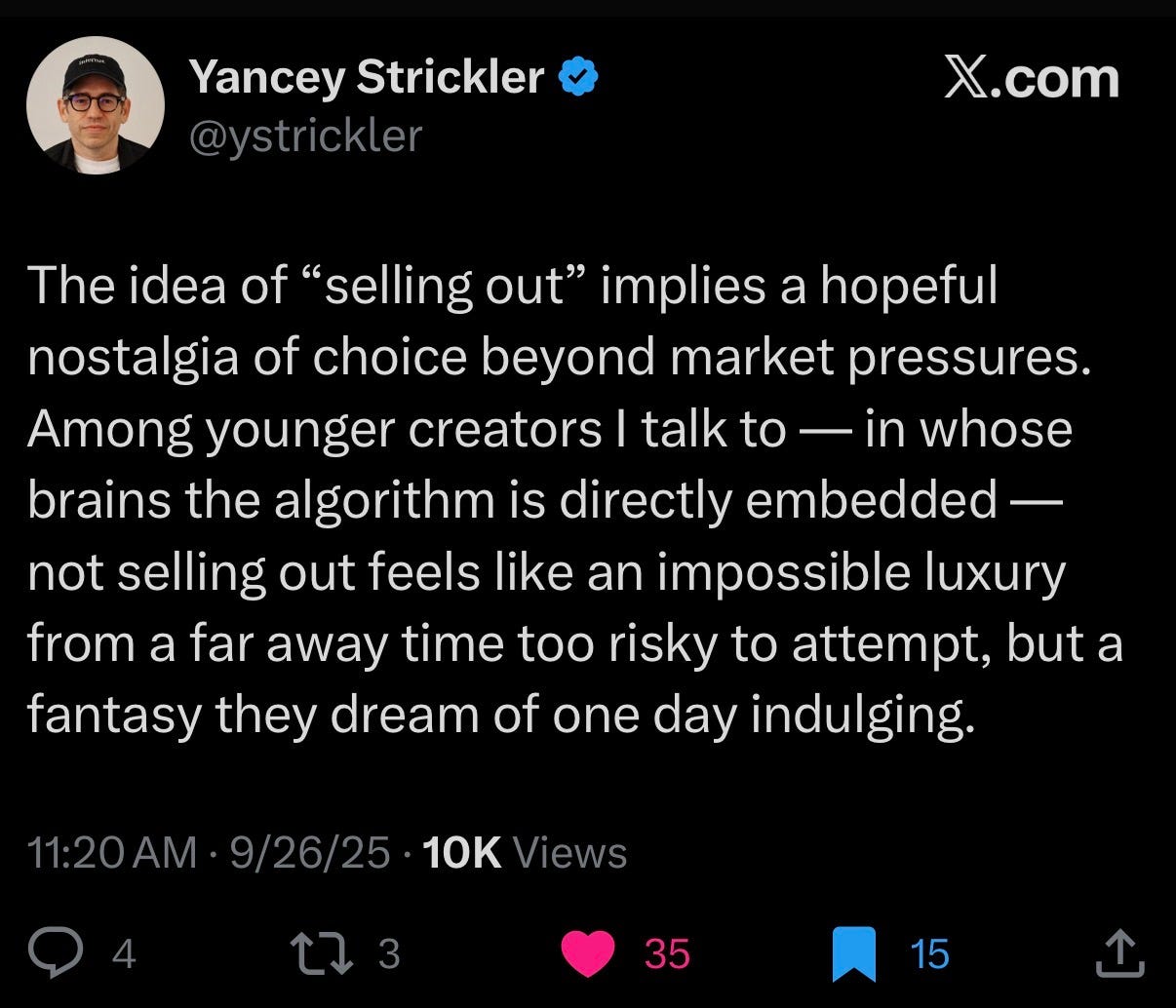

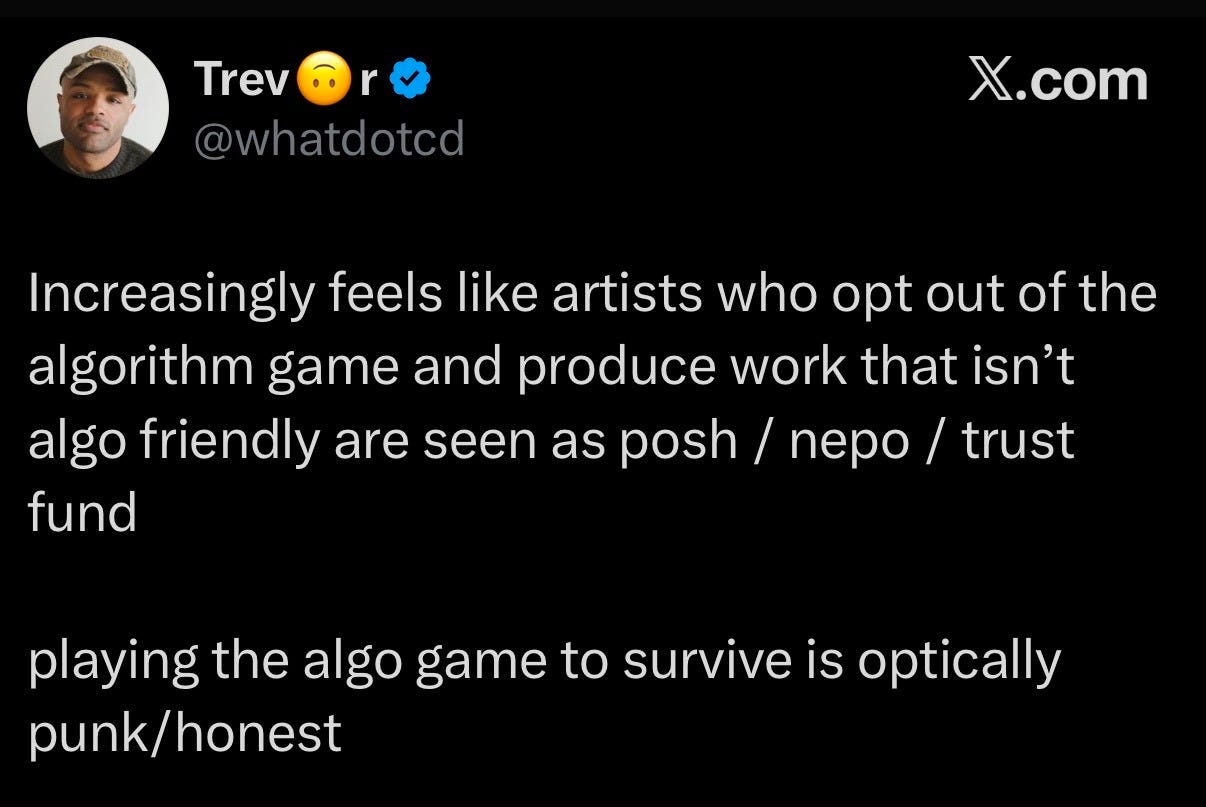

A couple more examples: cofounder of Kickstarter Yancey Strikler and founder of Brud Trevor McFedries (he and his team created the fictional influencer Lil Miquela) see the anti-sellout discourse as outdated, while producing work for the algorithm and making some money in the process is punk.

And finally, Emily Sundberg of Feed Me offers some great related insight in a Bloomberg podcast interview (that narrowly characterizes her as a Gen Z-soothsayer):

[Host]: I wanted to talk about Gen Z and capitalism. Because I feel like millennials and maybe Gen X, but millennials in particular had this love/hate relationship [with capitalism]. [They] sort of apologized for wanting money and were sort of ambivalent about it. And I get the impression that the younger generation is much more comfortable with [saying] “yeah we want to make a ton of money”

[Emily Sundberg]: Yeah, selling out is cool. I think one thing that is very clear about Gen Z is they’ve repeatedly been told: nobody is coming to save you. You’re going to graduate into a job market that barely exists. And if you get a job, you might not even have a desk or an office to go into…You hear this sense of: get the bag while the world is still here to make some money out of it.