Why do creatives hate money?

Commercialization and the sanctity of ideas

The starving artist, the tortured genius, the folk hero, the bohemian, the auteur, the prodigy, the enfant terrible. History is filled with unconventional creative people bucking trends to bring their unique visions of reality to life.

Across visual art, fashion, music, film, and literature, you’ll find countless books and documentaries detailing the lives of people who worked themselves to death to realize their ideas. These stories provide solace to those who haven’t yet made it. Your continued struggle is just a sign that you walk the same path as the renegades before you. And even if you don’t succeed in life, there’s always recognition after death, as with Van Gogh, who died broke and nameless, having sold no more than a couple of paintings.

The great myths of the starving artist can be validating. It’s not that my ideas are bad, it’s that I’m misunderstood. It’s not that I don’t know my audience, it’s that I’m ahead of my time. It’s a relief to pin your failures on the algorithm, the suits, the industry, or simply capitalism.

This is reinforced by the belief that the creative process is sacrosanct. In his widely read book on creativity, Rick Rubin says “without the spiritual component, the artist works with a crucial disadvantage.” For many creatives, an idea is like an irritant in an oyster. Leave a bit of grit or stray tissue undisturbed within its shell and the oyster builds layers until a pearl forms. Considering something as lowly as the audience or marketability can feel tantamount to prying open that shell and crushing it on the seafloor before the pearl has had a chance to emerge.

If ideas are sacred then earthly sacrifices are a necessary part of the creative process. F. Scott Fitzgerald may have drank himself sick and died at 44 before anyone had even heard of The Great Gatsby, but neglecting your health or family is increasingly passé with the turn of the century. Work/life balance entered the popular lexicon in the 2000s. Basecamp founders David Heinemeier Hansson and Jason Fried exemplify this shift in their 2018 book It Doesn’t Have to Be Crazy at Work:

[…] long hours, excessive busyness, and lack of sleep have become a badge of honor for many people these days. Sustained exhaustion is not a badge of honor, it’s a mark of stupidity.

Perhaps the days of witnessing your colleagues die from stress-induced heart attacks, as told in the recent Apple In China, are waning. But there is still honor to be found in one remaining sacrificial lamb…money.

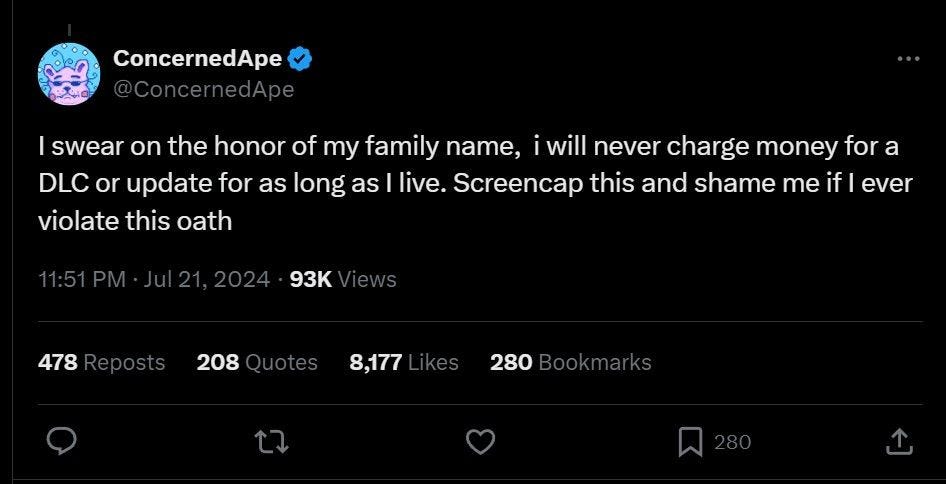

Stardew Valley creator Eric Barone is one of many in the indie games universe who have publicly expressed indifference or animosity toward money. When asked how much Stardew Valley updates or DLC would cost he said:

Nothing. It’s just like, I don’t care. I don’t care about money that much to be honest. I’m not trying to virtue signal, but I honestly don’t care about money that much. It’s never been the driving, motivating factor. What I care about is people loving the game.

As of 2024, 41 million copies of Stardew Valley have been sold. Rough estimates put Barone’s revenue from the game somewhere in the ballpark of $500 million. This idea that financial sacrifice is honorable can be found throughout contemporary creative culture. For established game developers, expectations of financial success can feel like unnecessary pressure, as Lucas Pope explains in connection to his recent game for the Playdate handheld console titled Mars After Midnight.

There's a lot of expectation attached to anything I do now. There's a lot of pressure following up Papers, Please, and Obra Dinn, and making something else that everyone's going to love. With the Playdate, it lowers the temperature on that expectation, especially because I made it clear this is a game I'm making for my kids, which is aimed at kids. That part is worth a lot more than just money or sales.

Many creatives share the feeling that some ideas are worth pursuing for a whole host of reasons other than money. This attitude is embodied by even the most inexperienced creatives. And it is implicit in arts education. The NYU Game Design BFA, which describes itself as “a well-rounded, interdisciplinary degree,” includes just one elective on the business side of making games. This course is offered not through the games department, but through NYU Stern’s Marketing Department with only a few reserved seats for game design students.

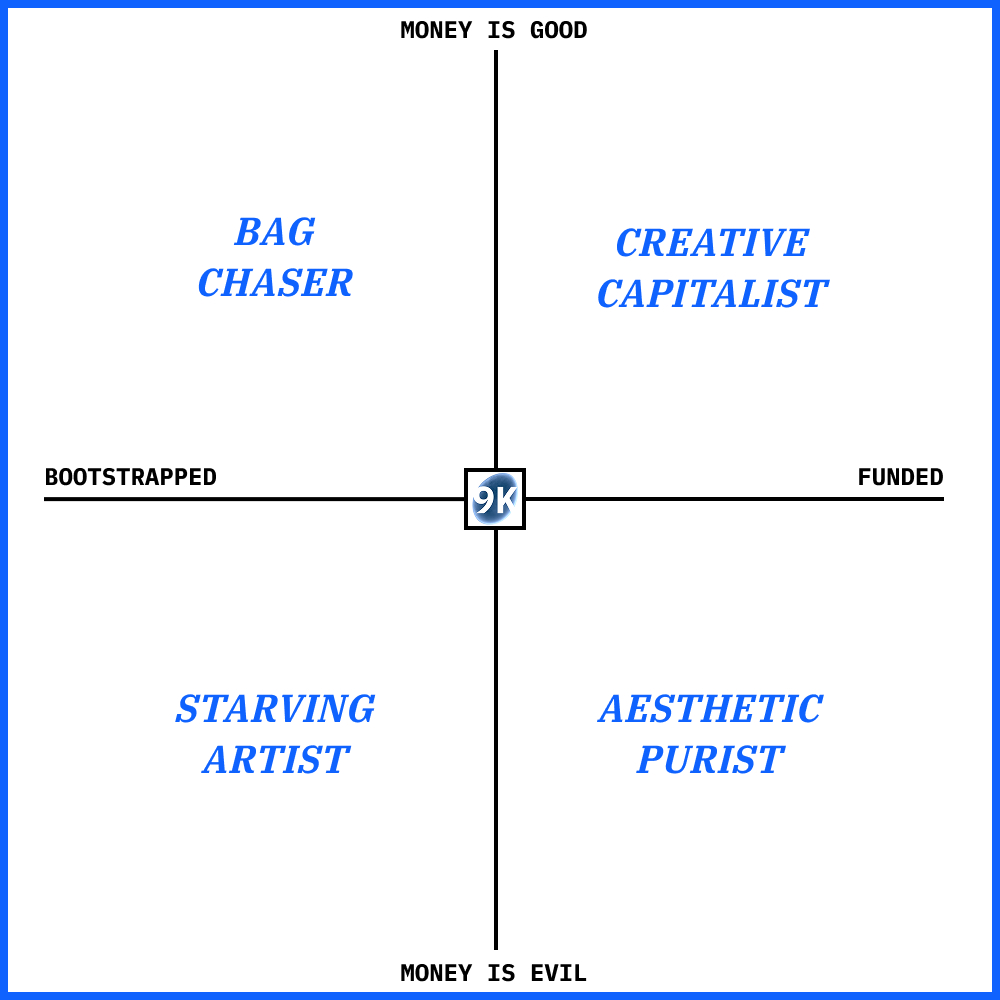

Many prefer to ignore the money side of things. They see it as a necessary evil in the way of true creative expression. As Joost van Dreunen, professor of said course at NYU, discusses in his book on the business of games titled One Up:

In my role as a teacher at New York University’s Game Center and the Stern School of Business, I’ve repeatedly observed the tendency among aspiring creatives to sacrifice any financial expectations to see their creative vision become reality. All too often, when asked how they would fund their proposed game company, my students answered they’d just eat ramen for six months. This idealized notion of the bohemian creative is a common one. But it is also incredibly naive.

The industry carries part of the blame: many of its professionals abhor conversations about money. They hold to the dogma that “money is evil” and insist that it is merely a by-product of their creative effort rather than a foundational principle of the for-profit activity in which they find themselves involved. Where technical challenges generally are met with enthusiasm, any financial limitations are considered unworthy. In my experience, the mere mention of any of its manifestations (e.g., corporate office, the suits, investors, or quarterly review) immediately provokes a brief ceremony of overt collective disdain during which everyone sides with creativity and distances themselves from the mundanity of money.

How did creative people come to believe that money is evil, their ideas are sacred, commercialization is the enemy, and total sacrifice, including months of surviving on instant noodles, is necessary if you want to realize your ideas?

I worked in the arts for 15 years and worked with many artists who shared this sentiment. Some years ago I worked on a project called [REDACTED]. It was a highly technical and scientific music concert and live performance. It was conceptually very unique. And for many of the venues we negotiated with across North America, Europe, Asia, and Australia, it was too unique. With 10 tons of custom equipment on stage, the setup was also high-risk from an insurance standpoint. Any failure would have been disastrous for a venue hosting the project.

The artists were incredibly dedicated in realizing this project, they had been working on it for over 6 years before they hired us to produce it. We managed to put together a world tour despite apprehension from a number of venues. After all the costs surrounding shipping the equipment, insurance, modest accommodations and fees for the performers, the show barely broke even. The artists were so attached to their ideas that they remained blind to the financial risks inherent to the project. The group continued to tour the work without our involvement. A year later, while performing at a venue in Europe, disaster struck. One of the pieces of equipment malfunctioned and the venue was completely ruined. The artists went on to file for bankruptcy.

When I began making games and getting a feel for the industry, I thought things would be different. Games are a highly industrialized medium. As opposed to touring experimental live performance, there’s no uncertainty that games are commercial products. Surely even indie developers must do market research and risk analysis, I thought. But, as I detailed in my recent post on 50 things for game developers, resources are few and far between when in comes to the business side of games. Perhaps I underestimated the influence that the “games as art” discourse has had on indie games.

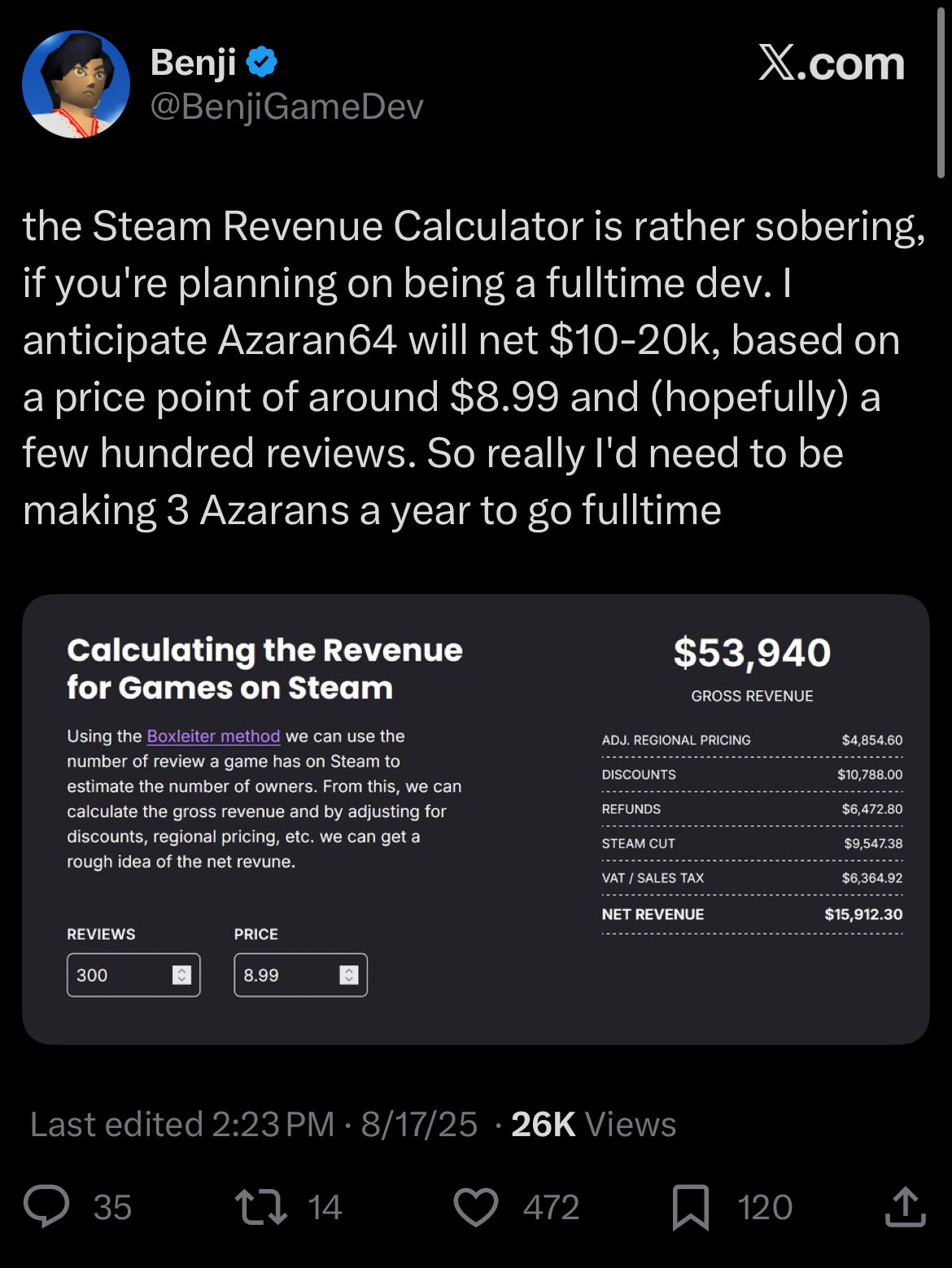

The average indie developer doesn’t realize that the median gross revenue for a 3D platformer on Steam is just $230. It’s not that there aren’t successes. There are 377 games 3D platformers that grossed over $100K according to data from GameDiscoverCo, but there are over 5,000 3D platformers that failed to surpass $20K in gross revenue. Most game developers come to this realization silently, tail between their legs, after releasing their first game.

Part of the challenge is, market research can be sobering and boring. It’s much easier to bask in the excitement of your latest greatest idea. You might even find yourself losing that spark you first felt if you dare evaluate your ideas for marketability.

I experienced this while making my first game, which I’ve written about previously. We became obsessed with our sacred ideas, gathering books and references and making mood boards. When it came to being realistic about the cost of implementing our ideas and the overall appeal for the kinds of players we were looking to reach, we were resistant. We didn’t want to kill our momentum and excitement each time we realized our latest concept or prototype would probably have a hard time finding an audience. After a failed launch the studio drastically downsized and I was laid off.

I believe there’s a way to thread the needle between the joy of creative expression and the reality of the games market. It’s just another creative muscle you’ve got to build, and eventually learn to flex. Creator of the horror game Home Safety Hotline (which I wrote about in my recent Steam Report on Computer Use games) shares a similar perspective in a Patreon post titled “Why I love marketing” saying:

I know a lot of creative people who would balk at the idea of considering things like hooks, target audiences, and industry trends when conceptualizing ideas for their art. I can see how it could feel like being your own cynical CEO, barging in on artists demanding changes to appease the mass market. But I don't really see it that way. I see it more as an interesting set of creative constraints, or like a creative prompt. In other words, I think it can actually fuel creativity. Our recent horror hit, Home Safety Hotline was a game concept born almost entirely of these kinds of creative constraints!

We should sit down and figure out the equation to luck + exceptionalism + perseverance + ethics that produce successful games. Can’t be that hard 🫠

While we venerate the few folks that brought their creative works to life at any cost, I wonder how many people don't achieve their dreams due to their own self-imposed barriers (not wanting to fairly implement pricing). I've been thinking a lot about the board game industry for the same reason: design is fun and flashy, business is for specialized folks (read: not designers). I wonder if we've specialized too far?

Great post, thanks for sharing!